My View of Glocks

My View of Glocks

October 26, 2009

History Lesson

In the early 1980s, police departments worldwide started pining for more firepower in their service weapons.

The reasoning behind this is still suspect: if you’re not HITTING your target, do you really need the capability for what amounts to suppressive fire, in a civilian environment?

In 2005, for instance, a pickup truck went down what amounted to a police gauntlet in a residential neighborhood in Los Angeles. Of some 120 rounds fired by over a dozen cops, only two hit the suspect, and the suspect walked away from the scene! The rest of the bullets were found embedded throughout the neighborhood, near children’s bedrooms, etc. It is a miracle no civilians were hit. The logical remedy is better tactics and better shooting (and, indeed, some police departments, such as the Austin Police Department, are investing in portable gun ranges, to help keep remote officers current), not more firepower. But I digress.

Modern revolvers have a nice characteristic: they’re very safe, and most can be used in two modes: single-action and double-action. In single-action mode on a revolver, the hammer is manually pulled back by the thumb, before the trigger is pulled by the forefinger, which fires the pistol. In double-action mode, the hammer starts down, and the pulling of the trigger pulls the hammer back automatically and then releases the hammer while it’s still in transit, which causes it to fire the pistol.

The force involved in double-action mode is about twice that in single-action mode. The trigger must also travel a much longer distance, as much as 1 inch vs. 1/16th inch for single-action mode. So the WORK, using the physics term, to fire in double-action mode can be up to 32 times higher. This higher work minimizes the chance of accidental firings by something hitting the trigger, whether an obstruction or a nervous finger.

This, along with other safety aids, such as an inertial firing pin, makes carrying a revolver hammer-down and in double-action mode a pretty safe proposition: safe to carry and safe for quick action in case the gun is needed. So safe, in fact, that few, if any, revolvers in manufacture have a safety.

For nearly a century, revolvers were the preferred weapon of police departments.

Pistols (“semi-automatics”) in the U.S. before the 1980s, by and large, did not have the double-action feature. The typical US pistol was a derivative of the pre-World War I M1911A1 or scaled variants using the same design principles. These guns had one firing mode: single-action only. This provides for a light trigger pull. This is fine for the military, since you probably have a fair idea when you’re going to need to pull the weapon and fire it. Pistols are also usually a fallback weapon in the military.

The M1911A1 actually has two safety devices: the hammer safety, and a grip trigger safety. So the pistol has to be held in order for the trigger to be pulled.

For an M1911A1-type gun used as a police service pistol or even as a defensive weapon, there is really only one credible firing mode: cocked, hammer back, safety on. If you need to fire, you draw, lower the safety, shoot. Or carry it hammer down unchambered, cock it, then shoot.

For cops, either approach involves one step too many and can introduce firing mishaps, or, worse, a non-firing situation, in which the bad guy gets to shoot first. Many many variants of the M1911A1 exist in the civil sector that seek to improve reliability and reduce operator errors, but these modifications did not receive nearly as much market penetration as revolvers.

Starting around World War II, designs such as the Walther P-38, began to be introduced in Europe which incorporated both a double-action mode AND a single-action mode. They also had clever mechanisms that would automatically and safely decock an armed pistol. Other innovations were also tried that sought to improve safety.

By the mid 1980s, the US military had abandoned the M1911A1 in favor of a new design, based on the Italian Beretta 92. This new gun was available in 9 mm, with around the same form factor as the M1911A1. The main functional differences were that it could be operated in both single and double action, it had a decocker built into the slide, and was easier to disassemble. It could also carry a lot more rounds. Many police departments snapped it up, but it almost immediately had a competitor, in the form of the Austrian Glock 17.

One last note: since single-action mode requires less trigger pressure, it’s possible for finer muscle control, thus yielding a more precise shot. It also allows for faster shooting. Double-action, conversely, being a heavier pull, tends to be less precise. If your DA pistol has a hammer, you can usually pull the hammer back to put it in single-action mode, or have the grosser (heavier) pull for snap shots. These snap shots will generally be at close ranges, where great precision is not required. The second shot in pistols is (almost) always single-action, unless the gun has been mutilated, er, modified, to keep it in double-action mode. Each shot in a modern revolver can be either single- or double-action, depending on whether one wants to pull the hammer back.

Glock to the Rescue

Glock, originally a toy company, introduced a revolutionary concept: why not carry an automatic like you would a revolver? Heresy! Moreso, remove all the doo-dads on the side: why would you need a decocker or safety, if you think about it? More heresy! Hammer? What hammer! Remove the hammer! Metal? Why do we need metal? Replace as much as we can with polymer plastics!

For generations of gun users accustomed to military weapons training, this was all unthinkable. So Glock’s marketing largely focused on debunking the fogies, and was hugely effective. Their marketing also insists that the Glock is a double-action-only pistol, no doubt to help penetrate the consciousness of those who had already made up their minds about single-action pistols (such as the M1911A1). Make no mistake: while technically the firing mechanism can be described as “double-action” in a highly technical sense, from an operator’s perspective the Glocks are a single-action-only pistol. This article describes the matter in more detail. Overall, the SA/DAO debate on Glocks is merely an indication of their very aggressive marketing.

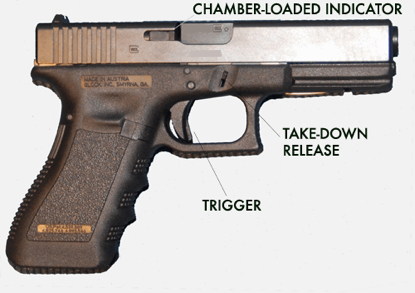

So we have a streamlined gun with no snags to catch on clothing, nothing to think about. Draw and shoot. Revolver-as-pistol:

Plus, the Glock was much lighter than many service pistols, due to the use of plastics in the lower section of the pistol (the grip and lower frame) (7 oz lighter, fully loaded, than an UNLOADED M1911A1). This was a relief to cops on the beat. It could also carry up to 17 rounds, 11 more than a revolver! More rounds, lighter gun.

From a design perspective, it was indeed safe. You can allegedly put a Glock in a paint shaker and it will not go off. They are also viewed as very rugged, since, due to the absence of many openings, there are few opportunities for sand and grit to get embedded.

And it was cheap, due to the plastics and simplified, advanced design. From one newspaper report, the Boston PD was offered them for under $280. This at a time when most pistols sold in the $500-$600 range.

Glock had a hit, outfitting beat cops worldwide with variants of the basic pistol. The pistol grew and adapted as police preferences changed. After an FBI debacle in Florida which caused a rethinking of ammunition, Glock jumped on the .40 S&W bandwagon, and helped stimulate adoption of that round. It inspired competitors to introduce their own “polymer pistols.”

Due to its marketing campaign, it had instilled a fervor in its adherents that was similar to those in the “Mac vs. PC” wars. It’s hard to have a rational conversation about Glocks. People who have them often LOVE them.

In the 80s through the 2000s, the military continued investigating advanced firearms, with competitions that resulted in the Heckler & Koch Model 23, and its smaller cousin, the USP (another polymer pistol). Sig Sauer made inroads on the American market, and had one of its guns, the P228, picked up by the military as the M11, as a standard sidearm. Walther introduced its own police pistol, the P99, which was comanufactured with Smith & Wesson. And Beretta got excellent penetration in police markets with the 92 FS (civilian M9), which was also co-manufactured with S&W. All of these featured visible hammers or strikers and the ability to safely and automatically decock the pistol.

In My Humble Opinion

I have fired all sorts of guns, including those fired above. I do not much care for the Glock design.

First off, I don't think they shoot well. My groupings are 2x larger with the Glock 17 than a Sig P228. I am a big believer in precision. I don’t know why the Glock 17 shoots more poorly, just that in my “weapons system” (eye/brain/hand/gun), the Sig P228 and USP do much better. And seem to do better with everyone I know who tries them.

Second, they're a single-action-only weapon. There's a much lighter trigger pull (remember, you generally don't want to carry a pistol unchambered. It's not “safe”: what if you need to use it -- why are you carrying a gun to begin with? You don’t want to be fumbling with cocking or arming it, spontaneously). There is a “twig safety” built into the trigger, to ensure a solid, wide object such as a finger is precisely pressing on it, but what if an object such as a finger is pressing on it inappropriately?

The Twigger (this is taken with the weapon cocked).

Thus, you should not carry them except in a holster designed for them. Too easy to squeeze one off.

Third. No safety, which would be nice as a safeguard for #3. It does not have either the grip safety of the M1911A1 or a lock-safety. This trigger safety is intended to stop an oblique pressure on the trigger from firing the pistol, but a direct (perpendicular) force will. One can imagine situations where an object can hit perpendicularly, with the gun not being properly handled (in a grip, under control).

Fourth, you have to carry them loaded and cocked, or you defeat the purpose. Since this puts them in single-action mode, there's a light trigger. So when you draw, there's a HIGHER chance of ACCIDENTALLY activating the trigger vs. the forces one would encounter in double-action mode on other pistols or revolvers. Voila, hole in foot/suspect/innocent bystander. Big problem, lots of paperwork. I also believe there’s a higher chance of NERVOUSLY shooting a weapon in single-action mode. If you’re skulking around your house looking for a burglar, wouldn’t you rather have slightly more resistance, giving you that last chance to make sure that blur is a bad guy, and not just jerk one off and kill your 8-year-old? Combat situations are tense: vision goes down the drain, and your reflexes are enhanced. I argue it’s safer in such situations to carry a weapon with a heavier trigger pull prior to active engagement. Similar arguments can be made for cops investigating darkened environments.

Fifth, there is no hammer or striker indicator to definitively show you whether you’re cocked and armed. There is a chamber loaded indicator, however. And presumably if the chamber is loaded, you’re cocked. This is a relatively small protrusion on the side of the slide. This approach is also generally available on other types of pistols, and is generally not used much by experienced users, who prefer to move the slide back to peek into the chamber. Since you're already cocked, this provides yet another opportunity for an errant finger to hit the single-action trigger.

Sixth, there is no de-cocking/safety mechanism. Remember, you're cocked and ready to go. Too easy, again, for a naive or out-of-practice user hit the trigger and fire one off as they’re safety-ing the weapon. With other guns (Sig), you can safely decock the gun, putting the weapon into double-action mode, requiring much heavier trigger forces, before ejecting the magazine and cycling the slide to remove the chambered round. It's safer.

There is an anecdotal “record” of accidental Glock discharges while handling the weapon, and a Google or YouTube search do indeed turn up a fair share, the results of which seem invariably to boil down to “fix it in training.” While much of the “fix it in training” campaign has led to better gun-handling in general, this appears to speak to the flaw in the overall design.

Cops, gangsters, and movie producers seem to love Glocks, but I wouldn't recommend them — OR their polymer cousins; I’m not picking on Glock per se, just their product’s design elements -- for anyone who doesn't know a lot about guns or work with them regularly. As one commenter on a gun forum put it, it is definitely not a “first gun.”

As with the Mac vs. PC wars, there is no convincing the converted. I mainly put this page together to try to explain a complex issue to potential gun owners. I claim no mystical knowledge: I am not a cop, SEAL, spy, mountie, or arms instructor, and the opinions herein are merely my own, and worth exactly what you paid for them.

Text and images Copyright © 2009 by Robert Dorsett. All Rights Reserved. Permission to reproduce this article for non-commercial purposes is granted, provided that this disclaimer is included. Commercial requests may be made by going to http://www.dorsett.us and using the feedback link.

Silly wabbit, Glocks are for cops.

Ready for Double-Action Firing

Ready for Single-Action Firing

Not loaded and cocked

Loaded and cocked

Carry Mode

Firing Mode